I was recently critiqued on my notation style, by someone who knows their stuff— who also knows their stuff— and I got paranoid that I was writing in a stupid way, so I went to my library to re-check what other people actually do.

You may have noticed, I virtually always put drum set materials on one set of stems. It's a doctrinal thing I decided to follow a long time ago: the drum set is one instrument, what we play on it is one rhythm, using four limbs. It's a common way of writing, but not the only way. In the past, drum set music was generally written as if the different parts were being played by different people, like a band part for snare drum and bass drum.

It's a difficult problem, because the drums are not normally played by reading a mapped out drum part verbatim— most of what we play is basically improvised, possibly with a sketched out groove suggested by a drum chart. But in the practice room we need to read a lot more particular, complex things than we would normally see in a drum chart, and that's where judgments about style come in, with the concerns being the best way to render an idea for the purposes of the materials.

So let's check out what is done in some some drumming library favorites (and otherwise):

Jim Chapin - Advanced Techniques For The Modern Drummer - 1948

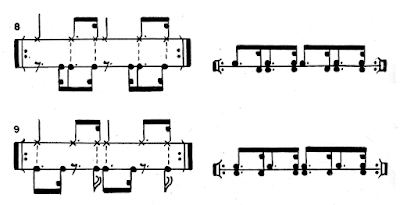

The earliest modern representation of drumming independence that I'm aware of. He writes the main exercises both with the cymbal and snare drum and cymbal parts separately, but with them unified into a single rhythm, on a single set of stems:

And those are still the main ways drums are notated today. They each have advantages. The single-stem way for the reasons I gave above. The two-part way because it's clearer what rhythm we're doing with the independent part.

Rhythmic Patterns - Joe Cusatis - 1963

This kind of situation is more usual in older drum set notation— and it's totally barbaric and unreadable. At least the drums played with the hands are on the same stems.

This is kind of a long post— much more below the fold:

New Directions in Rhyhm - Joe Morello - 1963

Here's a traditional engraving solution to drum set notation, on a relatively big-budget drum book of the time.

A problem I have with this book is that swing 8th notes are notated three different ways— as dotted 8th-16ths, as regular 8th notes, to be played with a swing interpretation, and as a triplet with a rest on the middle partial. There may be reasons to use each of those, at different times, but this book has them coexisting within the same exercise. Like on exercise 40 here, the snare drum and cymbal on beat 2 of both measures are all meant to be played the same way:

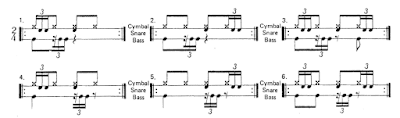

Realistic Rock - Carmine Appice - 1972

This book was ubiquitous when I was young, though I didn't know anybody who actually used it. I suspect the main thing it accomplished was to turn drummers off to reading, and popularize the idea that it's “too hard.”

Here each part of the drum set is written as an independent rhythm, when they really should be connected— the cymbal rhythm plus those partial triplets on the drums form one complete 16th note triplet:

On the expanded staff he's using when you do connect the parts that are clearly connected to each other, you get these ridiculously long stems, and the result is no easier to read than the other thing:

The content is not terrible, but it scrambles your brain just looking at that junk, and repels you from wanting to spend any time with it.

Charles Dowd - A Funky Primer - 1975

It's an old book now, but decent, and still in wide use. The notation style is forward-looking by, by my thinking, for putting everything on one set of stems. Here's the same type of thing we saw in Realistic Rock, rationally notated on a single set of stems:

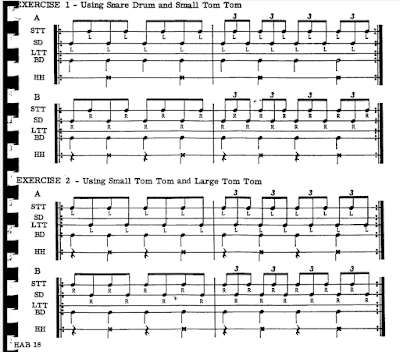

Basic Drumming - Joel Rothman - 1983

Rothman generally puts the bass drum on its own line of music, which is the method favored by the person who criticized my way. It's fine, it has its benefits, and I use this book quite often, on my own, and with my students.

Looking at this, it's very clear what the bass drum rhythm is, by itself. It's less instantly clear how the parts correspond, and what the combined rhythm of all the parts is. Mature readers have no problem with it, less experienced students have to analyze it a bit:

And again, the same kind of 16th triplet things, we saw above, with the hands on one set of stems, and the bass drum on another. It's not bad.

Steve Houghton - Studio And Big Band Drumming - 1985

Houghton basically does what I do, putting all the notes on one set of stems. He also flattens all his beams— except in that rock groove— which I also do.

Noting that my style was criticized for readability, but this book, which is all about chart reading, uses basically the same style as I do. Part of the criticism too was that another method— with hands and feet on different stems— was the default “industry-wide”; Houghton's book clearly indicates a different standard, if only for practice room materials. With the actual chart examples in this book, to the extent that grooves are written out at all (they're really only sketched out), they are written with hands and feet on different stems.

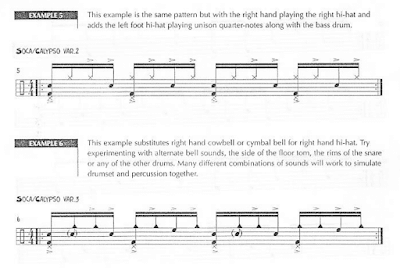

David Garibaldi - The Funky Beat - 1996

Generally everything is on one set of stems here— I don't like that he stretches a single measure across the whole page, but many of the beats here are rather dense, with a lot of dynamic markings. We'll see more of that in a moment.

Beyond Bop Drumming - John Riley - 1997

Riley does a variety of things, depending on the context and content. When there's a repeating part involved, the feet may be written on their own stems. Where there's more complex or non-repetitive foot activity, like in a transcription, he puts everything on one set of stems:

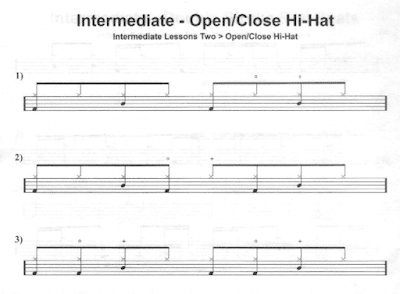

Jared Falk - Rock Drumming System - Intermediate and Advanced books

This not any kind of major work, but Falk's media company, Drumeo, is popular online, so his stuff gets used by a lot of people. I include it as an example of how drumming literature degrades as it gets taken over by online media personalities, who are not professional musicians and teachers.

Throughout these books, I get the feeling that a lot of style decisions were left to the notation software— whatever the software default was. He puts everything on one set of stems, which is fine. Here he tries to make a single measure of 4/4 time “easy” to read by stretching it across an entire 8 1/2" x 11" page:

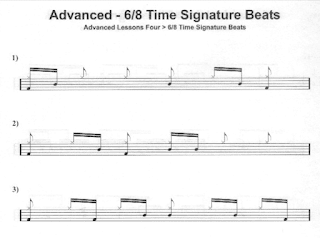

It doesn't help. In the “advanced” book, as he gets into more complex rhythms, we get some real atrocities:

That's trash as a musical idea, but we're focused on notation style... in which aspect it is also trash. I'm sorry.

Basically, we get egregious errors whenever any kind of editorial decision needs to be made about how to write something. Here are some “advanced” beats in 6/8 time, written “in 6”, with none of the 8ths beamed together, which is totally ridiculous:

I've never seen that done. Maybe in some vocal music, somewhere.

I want to make a distinction here: this is the first instance of a problematic style coming from incompetence on the part of the author. Most of the previous examples were done when there was no established style, and people were doing their best to invent one that made sense. Or they were doing it with a deliberate purpose. And before computers, drum authors often had to work with an engraver or copyist, if they didn't write the book by hand themselves. The labor and costs associated with that were real limitations— if you don't like the way the engraving house handled your hand written manuscript, you might not be able to afford to have them re-do it.

So, there. Someone had me in a panic for a minute. Had I sunk 10 years of work into a goofy notation system? No. What I do is what a lot of people do. Everybody relax. Except that one guy: stop relaxing, and learn how to write.

2 comments:

The goal of notation should be to make it as easy to read as possible, so that you can translate it into sound in an uncomplicated way.

However, there is no one way that works for everything.

That's why I'm more with the way it is in the Riley books.

If there is an ostinato, it is sometimes better to write it separately, unless it is important to see where the beats coincide.

People get lazy because they trust the notation apps and tend not to think for themselves.

But my default is also the One Stem notation, from which I only deviate if another solution makes it easier.

In my opinion, you usually do a great job of writing things in a very readable way.

Thanks Michael-- I think my worst offenses are on the transcriptions-- a lot of them are pretty jammed up. Too many measures on a line, and too many articulations/dynamic markings.

There are probably some cases where something would be more readable for you or me if I split up the parts, or omitted a repeating part-- usually I have a specific purpose in mind, or a specific student, or level of student. And I work pretty fast, so there have got to be some times when I'd do something different if I was submitting it to Down Beat or something.

Post a Comment