There have been a whole raft of people asking for transcriptions over on the

Drummerworld.com forum, so I thought this would be a good time for me to write up my long-intended little tutorial on the subject. If you read this and wonder if it's worth the trouble, you might also want to read my recent

Why We Transcribe.

When I was what I imagine is your age, all I had to work with was a cheap cassette player with crappy headphones, or, God help me, a turntable (with no 16rpm). Happily, today there are computer tools that make the job literally a million times easier than it was for me back in the 80's and 90's. There are programs you can buy (Transcribe is a good one), but we'll be using the open-source

Audacity, which is free to download and use (it is also spyware and other BS-free, so no worries there).

So, read on for my recommended procedure and tips. I haven't covered every single thing, but you'll develop your own methods as you work.

-

Don't be frightened. This is the sort of thing you can only learn to do by doing it, and making mistakes. Just dive in, and take it one note at a time. No one will laugh at you if you screw up royally.

-

Pick a tune. You've never done this before, so pick something easy- something with an straightforward drum part that is easy to hear in the mix. You are not obligated to do an entire piece- just getting one section, or one verse and chorus would be a good start.

-

Get Audacity. Install it on your computer and open the audio file you want to transcribe in it.

- Hit play and

listen and count through the piece. Determine the time signature. Hopefully you're starting with something in 4/4. If you can't figure it out, pick a different tune.

- As you listen and count through the track,

hit Control-M on your keyboard on every beat 1. This will lay down a marker which will make it easy for you to select one bar at a time to transcribe.

-

Prepare your notebook. Use manuscript paper- music paper. Put barlines in so you have four measures per staff, all the way down the page. To help make your measures even, put your first barline in the middle of the staff, then add the rest. Work in pencil.

- Back in Audacity,

highlight the first measure of music by clicking and dragging from one marker to the next.

- Hold down the shift key while pressing the play button with your mouse to

listen to the first measure as a loop.

-

Write out the drum part for that measure. Often this is easier said than done, which is the whole point of this. Here are some suggestions:

- Put in noteheads first, add stems and beams last. Stems and beams "finish" the measure.

- As you sketch out the measure, place your beats proportionally. Beat 1 should be at the beginning of the measure, beat 3 should be in the middle, beat 2 should be evenly spaced between the 1 and 3, etc.

- Do the obvious things first, and the difficult things last. If there is clearly a crash on 1, snare hits on 2 and 4, 8th notes on the hihat, but something you don't quite get in the bass drum, write in those other parts first, then figure out the bass.

- Tackle that challenging bass drum (or whatever) part one note at a time, starting with the obvious ones. If none of them are obvious to you, figure out where the first note falls, and take them in order.

- Try listening to the measure all the way through, one voice at a time. Start with the easiest or most repetitive one- maybe the cymbal or hihat.

- If the tempo is too fast for you to hear what's happening, in Audacity go to "effects>tempo change" and use the little plug-in to slow down the tempo. If you find it's too slow/not slow enough, hit Control-Z and try again. After you finish with the measure, hit Control-Z to bring the measure back to its original tempo.

- Simplify the instrument. Unless they are very different in sound, don't worry about differentiating between multiple crash cymbals- use one or maybe two lines, if you must. Same goes for toms- don't sweat it if a drummer has so many toms that you can't tell them apart.

- After you get the notes in place, and add your stems and beams, go back and listen at regular speed and add dynamics and articulations.

- Simplify internal dynamics and articulations. Some drummers (cough *Elvin Jones*) may play multiple levels of accents, regular notes, and ghost notes, multiple durations of buzzes, and so on. Keep your transcription playable by restricting yourself to 1) regular-volume notes, 2) accents, 3) housetop accents, and ghost notes (I mark these by putting parentheses around the note). Most of your notes should be un-accented and un-ghosted, if possible.

- If you hit anything that doesn't make sense, feel free to "resolve" it to something you can play, or move on. Don't get hung up.

- Here are some suggestions for

when you hit something that seems too difficult for you:

- Use siege warfare tactics- isolate and infiltrate. Determine where the difficult part starts and ends, then locate and attack the vulnerable "easy" parts.

- Start the playback before the beginning of the hard lick to establish the tempo.

- Listen to the accents to see if you can get a sense of how the passage breaks down internally.

- Try picking out the rhythm of one voice and fill in the rest around it.

- You may have to use the brute-force method of stopping the playback quickly after the first note of the hard lick. Then let it run through two notes, then three, and so on. Once you get the sequence of notes, you may have to go back and correct the rhythm.

- As you move through the piece,

use shorthand where possible- one-measure, two-measure and section repeats, or slash marks (Google it- indicates to play time in the style of the piece- you can use them if the drum part is very repetitive).

-

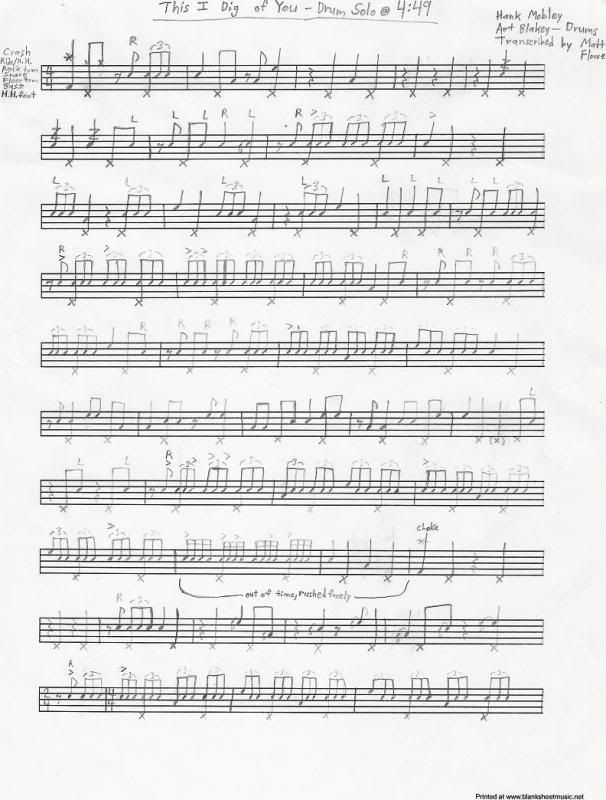

When you complete your transcription, mark it with the title of the piece, the composer or songwriter's name, the drummer, the recording artist, the album and record label, and the start time (if you've only done a section of the piece). And don't forget to give yourself a "Transcribed by..." credit and a copyright date.

That's it. I've got my own transcribing to do- have fun and be persistent in figuring things out.