Another long one: Joe Henderson with Al Foster and Dave Holland:

Tuesday, January 31, 2012

Monday, January 30, 2012

VOQOTD: Elvin

“Don’t ask me to show you anything, because if I could show you, we would all be Max Roach.”

- Elvin Jones, from part 2 of Ethan Iverson's Billy Hart interview

- Elvin Jones, from part 2 of Ethan Iverson's Billy Hart interview

Ethan Iverson interview with Billy Hart

Here's part of another great interview by the Bad Plus' Ethan Iverson, this time with Billy Hart:

Miles and Tony

Tony, for his age, seemed to me more thorough in the study of the jazz tradition of drumming than anybody I’ve ever come across. That doesn’t mean there aren’t other guys. But the more I learned, the more I realized that he had somehow gotten that history together. And it is not just patterns, it’s the reason why… I guess it would be in any kind of musical tradition, certain chords or accents or whatever present an emotion that been tried and true over a length of time, which I guess “speaks” or is traditionally accurate or correct. Tony had that. It wasn’t just that he played this rhythm or pattern, it was that the pattern belonged there traditionally. A lot of people today might play a Tony Williams pattern, but they play it just because they heard it…they don’t know why or how it works.

There is that video you played me of the Miles Davis quintet with Herbie and Ron playing “Autumn Leaves.” There are some tensions in the piano and bass, and Tony responds by playing a simple shuffle on the snare and cymbal, which is kind of an advanced response to the tension.

Except that it so correct! You can see Miles is immediately influenced and affected emotionally. And then you back to Philly Joe or anybody, hear them do it, and go, “oh right.” It’s like a change of color or a heightened intensity. (As opposed to starting a tune that way---if you start a tune there, you have to stay there.)

One of the interesting things about the Miles band is that there were a lot of details about the tunes that incoming members have to learn, like the cymbal beat and piano tremolos on “All Blues.” Tony and Herbie interpreted those parts in their own way, but still they clearly knew the details.

That’s something else that Tony said. Someone asked him about getting the gig with Miles just before he was 17 years old. There must have been other good drummers, right? Tony said, “Hard to know. I’d like to ask Miles myself. I can’t say that I was better than anybody else. But I was definitely prepared for the gig. There was nothing Miles could play that I didn’t already know.”

Keep reading- important stuff about time after the break:

Miles and Tony

Tony, for his age, seemed to me more thorough in the study of the jazz tradition of drumming than anybody I’ve ever come across. That doesn’t mean there aren’t other guys. But the more I learned, the more I realized that he had somehow gotten that history together. And it is not just patterns, it’s the reason why… I guess it would be in any kind of musical tradition, certain chords or accents or whatever present an emotion that been tried and true over a length of time, which I guess “speaks” or is traditionally accurate or correct. Tony had that. It wasn’t just that he played this rhythm or pattern, it was that the pattern belonged there traditionally. A lot of people today might play a Tony Williams pattern, but they play it just because they heard it…they don’t know why or how it works.

There is that video you played me of the Miles Davis quintet with Herbie and Ron playing “Autumn Leaves.” There are some tensions in the piano and bass, and Tony responds by playing a simple shuffle on the snare and cymbal, which is kind of an advanced response to the tension.

Except that it so correct! You can see Miles is immediately influenced and affected emotionally. And then you back to Philly Joe or anybody, hear them do it, and go, “oh right.” It’s like a change of color or a heightened intensity. (As opposed to starting a tune that way---if you start a tune there, you have to stay there.)

One of the interesting things about the Miles band is that there were a lot of details about the tunes that incoming members have to learn, like the cymbal beat and piano tremolos on “All Blues.” Tony and Herbie interpreted those parts in their own way, but still they clearly knew the details.

That’s something else that Tony said. Someone asked him about getting the gig with Miles just before he was 17 years old. There must have been other good drummers, right? Tony said, “Hard to know. I’d like to ask Miles myself. I can’t say that I was better than anybody else. But I was definitely prepared for the gig. There was nothing Miles could play that I didn’t already know.”

Keep reading- important stuff about time after the break:

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Saturday, January 28, 2012

Another new drumming blog

I'm really trying to put a finish on this bloody book of transcriptions this weekend (it's ending up being about 150 pages long), so while I'm fooling around with that, you can go check out (and bookmark, and blogroll) Chicago drummer Jeffrey Lien's new blog, The Drummers Way. So far his stuff is centered around very substantial teaching tips, transcriptions, and studio/pop/rock drumming. Very much looking forward to seeing how the blog develops. Go pay him a visit.

Friday, January 27, 2012

Pinstripes reconsidered

Here drummer and Modern Drummer writer T. Bruce Wittet takes another look at the now-humble Remo Pinstripe. For a good part of the 70's and 80's they were the drum head of choice for many, many players, until they went out of style in a big way in the early 90's. Their rise and fall tracks roughly from the beginning of Steve Gadd's massive popularity through the end of Dave Weckl's.

For good or ill, their long, funky tone and cushiony (taffy-like?) response shaped both my touch and musical approach to the toms for some time; when you tune them low as I did, they felt good and sounded best when you lay into them. You had to play through the head, which caused me to develop something of a funk drummer's touch. Even though, with two plies of mylar glued at the edge, they are inherently a muffled head, the body of their tone is long. Because of that slow response, your ear would tell you to play more single notes, and less, well, dense drummer junk.

So T. Bruce's big reveal relates to his first MD piece, a 1978 interview with Jack Dejohnette. Naturally, the heads Jack was using at the time:

For good or ill, their long, funky tone and cushiony (taffy-like?) response shaped both my touch and musical approach to the toms for some time; when you tune them low as I did, they felt good and sounded best when you lay into them. You had to play through the head, which caused me to develop something of a funk drummer's touch. Even though, with two plies of mylar glued at the edge, they are inherently a muffled head, the body of their tone is long. Because of that slow response, your ear would tell you to play more single notes, and less, well, dense drummer junk.

So T. Bruce's big reveal relates to his first MD piece, a 1978 interview with Jack Dejohnette. Naturally, the heads Jack was using at the time:

Clear Remo Pinstripes, oh yeah. And did he sound good! In the break between shows, we sat in figure-8 relative to my cassette recorder and I stumbled and blurted out questions I dearly needed to ask, throwing aside my script. One of these concerned the wonderful tom sound I’d just heard. Jack explained that these new heads, Pinstripes, were perfect because they muffled the circumference, and thus the weird overtones, allowing a more focused tone to emerge. He told me he preferred tuning them really tightly stating, “it’s a jazz tuning, that’s all”.

Thursday, January 26, 2012

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

Drum chart: Along Comes Mary by Cal Tjader

Pillaging the archives while I'm working on tour/book-related junk, I turned up another Cal Tjader drum chart, written by me a couple of years ago. I'll try to do more of these in the future- it's a nice alternative to complete transcriptions. The groove is a bright chacha all the way through.

Get pdf | get El Sonido Nuevo by Cal Tjader | get Along Comes Mary

YouTube audio after the break:

Get pdf | get El Sonido Nuevo by Cal Tjader | get Along Comes Mary

YouTube audio after the break:

Monday, January 23, 2012

Todd's Methods: Stick Control in 5

So much for writing nothing. I've been doing a lot of practicing in 5/4 lately- I've always quite sucked at it, frankly- and finally getting it together for real has been a curious process. Very different from 4/4 or 3/4, for not-obvious reasons. We'll go into that another time.

This method is so simple that I would be very surprised if it wasn't already in use, though I've never heard of it: you add a quarter note at the beginning, middle, or end of each exercise from the beginning of Stick Control.

Much of learning this meter involves learning some very "regular" patterns, with more emphasis on beat 1 than drummers of my, ahem, sophistication are usually comfortable with. This method is good for cracking that and getting at a more modern language. It works best at brighter tempos, in a fusion/funkish style, or the even-8th ECM feel, depending on how you accent and use the bass drum. Don't be too much of a mechanic in how you run these things; if something other than what I've written out falls under your hands easily, do it. The patterns all speak a little differently- try to find what each one is good for and develop it accordingly.

Get the pdf

This method is so simple that I would be very surprised if it wasn't already in use, though I've never heard of it: you add a quarter note at the beginning, middle, or end of each exercise from the beginning of Stick Control.

Much of learning this meter involves learning some very "regular" patterns, with more emphasis on beat 1 than drummers of my, ahem, sophistication are usually comfortable with. This method is good for cracking that and getting at a more modern language. It works best at brighter tempos, in a fusion/funkish style, or the even-8th ECM feel, depending on how you accent and use the bass drum. Don't be too much of a mechanic in how you run these things; if something other than what I've written out falls under your hands easily, do it. The patterns all speak a little differently- try to find what each one is good for and develop it accordingly.

Get the pdf

Sunday, January 22, 2012

DBMITW and news

We'll be on light posting for the next couple of days while I do a bunch of work on publicity for my new record of the music of Ornette Coleman, Little Played Little Bird (which you can pre-order in the side bar); and booking spring and fall Europe tours, and putting together volume one of "the book of the blog" for 2011.

That's right, that's not a twelve-word typo: Thanks to the magic of online publishing, you'll soon be able to purchase our materials from 2011 in book form for a very reasonable figure. Volume one will be around 100 pages of transcriptions, and volume two will cover practice materials- I haven't calculated the length yet. The cost will be less than you would spend in printer toner printing them all out yourself. Stay tuned...

In the mean time, enjoy some 1980-ish LA-style fusion with John Serry, featuring Carlos Vega- this is one of the first records I ever owned, which my brother handed down to me:

More of this old favorite after the break:

That's right, that's not a twelve-word typo: Thanks to the magic of online publishing, you'll soon be able to purchase our materials from 2011 in book form for a very reasonable figure. Volume one will be around 100 pages of transcriptions, and volume two will cover practice materials- I haven't calculated the length yet. The cost will be less than you would spend in printer toner printing them all out yourself. Stay tuned...

In the mean time, enjoy some 1980-ish LA-style fusion with John Serry, featuring Carlos Vega- this is one of the first records I ever owned, which my brother handed down to me:

More of this old favorite after the break:

Saturday, January 21, 2012

The club scene

Here's a great piece on understanding the, well, near-dead state of live music in clubs (professionally, anyway), and what musicians can begin to do about the situation, by LA pianist Dave Goldberg.

It opens:

Much of the focus is on educating club owners, but musicians also need to internalize concepts like this:

He makes this important point, on something which has long baffled me about the expectation that musicians to bring their own personal flash mob to each and every gig:

And even when an amateur group is able to pack the place with friends and family:

Every musician should read the entire piece and reorient their thinking about their relationship with clubs.

(h/t to clownbaby90 on Reddit)

It opens:

AS I’VE BEEN LOOKING FOR GIGS LATELY, I’ve never seen so many free and low paying gigs. Well the economy is bad, so I can understand that a little bit. However, it is no longer good enough for the musician to be willing to perform for little compensation. Now we are expected to also be the venue’s promoter. The expectations are that the band will not only provide great music, but also bring lots of people to their venue. It is now the band’s responsibility to make this happen, not the club owner.

Just the other day I was told by someone who owned a wine bar that they really liked our music and would love for us to play at their place. She then told me the gig paid $75 for a trio. Now $75 used to be bad money per person, let alone $75 for the whole band. It had to be a joke, right? No she was serious. But it didn’t end there. She then informed us we had to bring 25 people minimum. Didn’t even offer us extra money if we brought 25 people. I would have laughed other than it’s not the first time I’ve gotten this proposal from club owners.

Much of the focus is on educating club owners, but musicians also need to internalize concepts like this:

If you want great food, you hire a great chef. If you want great décor, you hire a great interior decorator. You expect these professionals to do their best at what you are hiring them to do. It needs to be the same with the band. You hire a great band and should expect great music. That should be the end of your expectations for the musicians. The music is another product for the venue to offer, no different from food or beverages.

He makes this important point, on something which has long baffled me about the expectation that musicians to bring their own personal flash mob to each and every gig:

When a venue opens it’s doors, it has to market itself. The club owner can’t expect people to just walk in the door. This has to be handled in a professional way. Do you really want to leave something so important up to a musician?

And even when an amateur group is able to pack the place with friends and family:

The crowd is following the band, not the venue. The next night you will have to start all over again. And the people that were starting to follow your venue, are now turned off because you just made them listen to a bad band. The goal should be to build a fan base of the venue. To get people that will trust that you will have good music in there every night. Instead you’ve soiled your reputation for a quick fix.

Every musician should read the entire piece and reorient their thinking about their relationship with clubs.

(h/t to clownbaby90 on Reddit)

Friday, January 20, 2012

All the grooves from Maggot Brain

Many of these are highly variable, so it may be presumptuous to declare that I'm giving you all the grooves from this record, but that's the name of the series... I guess that's what I get for picking subjects in my sleep (this came on the headphones last night). Anyway, here in broad strokes are the grooves from Funkadelic's epic Maggot Brain, with drumming by Tiki Fulwood:

UPDATE: Not only should I not pick topics in my sleep, I should not transcribe when I'm on my first cup of coffee: Hit It And Quit It makes much more sense with measure three as the 3/4 bar, and the last measure in 4/4. That's what it is, in fact. So get out your pencils and move that barline one beat to the left- I'll update the original when the book comes out in 2013.

Get the pdf | get Maggot Brain by Funkadelic

Select YouTube audio after the break:

UPDATE: Not only should I not pick topics in my sleep, I should not transcribe when I'm on my first cup of coffee: Hit It And Quit It makes much more sense with measure three as the 3/4 bar, and the last measure in 4/4. That's what it is, in fact. So get out your pencils and move that barline one beat to the left- I'll update the original when the book comes out in 2013.

Get the pdf | get Maggot Brain by Funkadelic

Select YouTube audio after the break:

Thursday, January 19, 2012

DBMITW: Gadd with Chick

I'm working on putting last year's transcriptions into book form today- which, thanks to the miracle of online publishing, should be available for you to purchase shortly. So you'll just have to enjoy these two recordings of Steve Gadd playing with Chick Corea. For many, many drummers these are two career-altering, life-changing tracks:

Get The Mad Hatter by Chick Corea

Get The Leprechaun by Chick Corea

Get The Mad Hatter by Chick Corea

Get The Leprechaun by Chick Corea

Wednesday, January 18, 2012

Other people say good things

It's a slow writing day for me, but there are lots of good things afoot at our brother drummer blogs right now:

@ Trap'd: Inspired by Art Taylor, Ted Warren outlines some easy things you can/should do to give tunes some shape. Here is a savagely-edited teaser- go read the entire piece:

Also see Warren's recent piece on transcribing and listening, where he says nice things about us.

@ The Melodic Drummer: Andrew Hare offers one burning post after another, this time dealing with the Philly Joe beat- go find out what it is. A nice companion to the Trap'd piece above is Hare's series on transitions, along with a post on endings.

@ Four on the Floor: Jon McCaslin has a ton of great little stuff. Read his Monday Morning Paradiddle for a, ahm, potpourri of good stuff- a number of well-selected clips, MLK on jazz, Elvin with Coltrane, Greg Hutchinson warming up, and more.

@ Trap'd: Inspired by Art Taylor, Ted Warren outlines some easy things you can/should do to give tunes some shape. Here is a savagely-edited teaser- go read the entire piece:

1. Rapid volume changes- One of the things I noticed that Art Taylor did in the tune I saw is that even though he didn't switch cymbals for each soloist, he did change the volume level of his cymbal throughout the piece to cause a texture change. [...]

2. Changing cymbals- This is probably the most common and easiest way of signally changes between soloists and sections, however, it is most effective when you know the form of the tune you're playing! [...]

3. Changing comping textures- Another great thing I noticed in the Art Taylor footage was how when he went from the Tenor to the piano solo, even though he didn't change cymbals he went from quite prominent bass drum/open snare comping to mainly a click on beat 4 and very quiet bass drum. [...]

4. Changing implements- Going from brushes to sticks is a great way to let the listener know the head is over and the soloing has started. [...]

5. A couple of more things about bass solos- Bass is not only usually the quietest thing in the band, it's also the instrument that gets lost most easily due to low frequencies being harder to hear. [...] So it's generally a good idea to thin out the texture of your timekeeping as well as the volume. Don't thin out the strength of the time or the commitment to the form though. [...]

Also see Warren's recent piece on transcribing and listening, where he says nice things about us.

@ The Melodic Drummer: Andrew Hare offers one burning post after another, this time dealing with the Philly Joe beat- go find out what it is. A nice companion to the Trap'd piece above is Hare's series on transitions, along with a post on endings.

@ Four on the Floor: Jon McCaslin has a ton of great little stuff. Read his Monday Morning Paradiddle for a, ahm, potpourri of good stuff- a number of well-selected clips, MLK on jazz, Elvin with Coltrane, Greg Hutchinson warming up, and more.

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

Paradiddle-diddle method for uptempo jazz

This is something I developed for both for getting some relief while playing fast tempos, and for doing a modern feel without getting your cymbal pattern lost in the weeds. The seed of the idea comes from Bob Moses (see "Non-independent method" in Drum Wisdom) and John Riley (see "Fast face-lift" in Jazz Drummer's Workshop). It's actually pretty straightforward, once you're able to read through this batch of syncopation exercises using the method outlined in the last post; first move your right hand to the ride cymbal, leaving the left on the snare, and add the hihat on the &s, with your foot:

We'll need to convert the 16th notes of the exercise to 8th notes, so one measure of 16ths becomes two measures of 8ths. If you can't do that instantly, start by counting 1-2-1-2 instead of 1-2-3-4:

Think of the 16th notes as 8th notes. Counting your fast tempos in a moderate 2 is actually preferable to counting a fast 4:

After the break I'll give a few options for the bass drum part.

We'll need to convert the 16th notes of the exercise to 8th notes, so one measure of 16ths becomes two measures of 8ths. If you can't do that instantly, start by counting 1-2-1-2 instead of 1-2-3-4:

Think of the 16th notes as 8th notes. Counting your fast tempos in a moderate 2 is actually preferable to counting a fast 4:

After the break I'll give a few options for the bass drum part.

Monday, January 16, 2012

Todd's paradiddle-diddle interpretation

This is the first practice method for the pages of syncopation exercises I posted the other day. Today I'll give it to you just for the hands only, then later I'll show you how I apply it to the drum set, first for uptempo jazz. As I mentioned, there are only three note values used (or their equivalent with ties or rests): dotted quarter notes, quarter notes, and single 8th notes.

For three-8th note durations:

For two-8th note durations:

For single 8ths:

I've given the sticking just on snare drum, and on snare drum and hihat to illustrate its shape a little better. Don't overplay the accents, particularly on the RRLL sticking- just put a little emphasis. This is a very right hand-heavy method- it's a good idea to also start it with the left.

Example after the break:

For three-8th note durations:

For two-8th note durations:

For single 8ths:

I've given the sticking just on snare drum, and on snare drum and hihat to illustrate its shape a little better. Don't overplay the accents, particularly on the RRLL sticking- just put a little emphasis. This is a very right hand-heavy method- it's a good idea to also start it with the left.

Example after the break:

Sunday, January 15, 2012

Dave Tough's Advanced Paradiddle Exercises

Here's an out-of-print classic, scanned and made available for download thanks to Denver drummer Todd Reid. God knows if it will ever be made commercially available again, or if anyone even owns the copyright, so I guess this isn't the world's worst pirating offense. In any case, if the book only exists in a few senior citizen drummers' libraries it's effectively dead, and that's unacceptable to me. It needs to survive as part of our literature. So here:

Get the book.

h/t to dmacc at DW

Get the book.

h/t to dmacc at DW

Saturday, January 14, 2012

Syncopation exercises with dotted quarter notes

This is one of many pages of original Syncopation variants I've written up, in this case restricted to combinations of dotted quarter notes, quarter notes, and single 8th notes. I've devised a few interpretive methods that work well within that limitation, which I'll be sharing, well, maybe real soon, since it looks like we're having a few snow days here in Portland...

Get the pdf

Get the pdf

Friday, January 13, 2012

Groove o' the day: Billy Cobham in 17/16

I present this just as a curiosity, because I've never encountered this meter anywhere before (maybe in a percussion ensemble piece?). But you can see how we usually deal with the odd #/16 meters; often they will be broken down into a regular meter + some 16ths. The solo section of Frank Zappa's Keep It Greasey, you'll remember, is in 19/16, interpreted as 4/4+3/16. Today's example, Spanish Moss from Billy Cobham's 1974 album Crosswinds, is in 17/16, played as 3/4+5/16 (with the 5/16 further broken down to 2+3/16).

Here's the main groove, plus a couple of more embellished versions that occur frequently throughout the piece:

Get Spectrum by Billy Cobham | get mp3

Here's the main groove, plus a couple of more embellished versions that occur frequently throughout the piece:

Get Spectrum by Billy Cobham | get mp3

Thursday, January 12, 2012

Drum! mag update

|

| See this issue for my last piece. |

Visit Drum! magazine online.

Tuesday, January 10, 2012

Batucada on the drum set

We haven't done anything new with samba in awhile, because I'm still digesting all of the stuff we've done previously. But here's something new that came up yesterday, using open and muffled tones on the bass drum to emulate the surdo. It would also be helpful to run the third surdo parts from O Batuque Carioca, as well as my bossa bass drum variations, and the standard dotted-8th/16th samba pattern with this. This feel combines well with samba cruzado, which we've discussed before.

Notes:

- Play the snare drum with the "tripteenth" feel; the '#' and the 'a' of each beat of 16ths line up almost exactly with the first and last notes of a triplet. Play with or without the buzz on the 'e', with sticks or brushes.

- Use either hihat pattern. The second pattern uses a closed note on beat 1, and a splash on beat 2.

- Play staccato bass drum notes as a dead stroke- bury the beater in the head to make a muffled sound. Play the tenuto notes as an open tone, allowing the beater to rebound. This works best with a drum with little or no muffling.

- Bass drum patterns with rests are preparatory studies. Patterns without rests are performance patterns.

- Also substitute dotted-8th/16th rhythm for the 8th notes or the 16th-8th-16th rhythm on the performance patterns.

Get the pdf

YouTube examples after the break:

Notes:

- Play the snare drum with the "tripteenth" feel; the '#' and the 'a' of each beat of 16ths line up almost exactly with the first and last notes of a triplet. Play with or without the buzz on the 'e', with sticks or brushes.

- Use either hihat pattern. The second pattern uses a closed note on beat 1, and a splash on beat 2.

- Play staccato bass drum notes as a dead stroke- bury the beater in the head to make a muffled sound. Play the tenuto notes as an open tone, allowing the beater to rebound. This works best with a drum with little or no muffling.

- Bass drum patterns with rests are preparatory studies. Patterns without rests are performance patterns.

- Also substitute dotted-8th/16th rhythm for the 8th notes or the 16th-8th-16th rhythm on the performance patterns.

Get the pdf

YouTube examples after the break:

Monday, January 09, 2012

...or, to just fail.

I would add:

- Think of your work as being in competition with that of all artists, everywhere, at all levels of the business, past and present.

- Imagine that your every creative move and decision is being judged by people better than you.

- Be dominated by your weaknesses. Be oblivious to your strengths.

h/t to Ed Domer and Universal Audio

Sunday, January 08, 2012

Another Drum! Magazine piece

Oh, hey, it looks like Drum! Magazine is going to publish another piece of mine, "Cross Rhythms Using Stone", which outlines a polyrhythmic application for using the 3/8 portions of Stick Control in 4/4, on the drum set. Just awaiting final confirmation and street date...

Transcription: three Philly Joe intros

Must do shorter, faster posts. That last one took way too many hours. Here:

Get the pdf

Get Dance of the Infidels | get Hank by Hank Mobley

Get I'll Never Smile Again | get Interplay by Bill Evans

Get Philly Mignon | get Here to Stay by Freddie Hubbard

YouTube audio after the break:

Get the pdf

Get Dance of the Infidels | get Hank by Hank Mobley

Get I'll Never Smile Again | get Interplay by Bill Evans

Get Philly Mignon | get Here to Stay by Freddie Hubbard

YouTube audio after the break:

Saturday, January 07, 2012

On “feathering” the bass drum

|

| what is this |

Apart from the word itself, what bothers me the most about that way of playing itself is that it's vestigial. It's left over from the days when the bass drum was played for the same reason anything is played: to be heard. Now we're doing something to not be heard, that you still have to learn to do as well as everything else you do, that's going to make you sound bad if you don't get it to the right level of inaudible perfection. We spend a lot of time eliminating non-functional elements from our playing, and our movements when playing, and this just seems completely contrary to that.

As I said, through the swing era, drummers played the bass drum to be heard. In the 1940s bop drummers de-emphasized it dramatically, but they kept doing it because that's how they knew how to play. More modern players, without the same swing background as many of the bop drummers, began dropping it out altogether. Maybe this debate over whether to play the bass drum, and how loud, was happening as this was all developing— I suspect the justifications for feathering it came later. All of these developments happened before I was born.

When I first began playing jazz in the 1980's, drumming as I knew it was in a very post-Tony Williams state. The sense I got from the best players I was around was that playing the bass drum that way was antiquated, and that in modern playing the time feel was centered in the cymbal and hihats; the bass drum and snare drum were for comping, punctuations, for funky/Latin feels, or as part of a texture (a la Elvin Jones). Playing quarters on the bass was regarded as an unsophisticated use of the instrument, and a big turn-off when it was abused... particularly by rock drummers, for whom it was a crutch. So, I've never played the bass drum as part of my time feel, except when playing shuffles, or in specifically very traditional swing settings.

Nevertheless: In recent years I've re-evaluated all of this somewhat, and I play more unaccented quarter notes than I used to. Understanding the traditional role of the bass drum is important, and you can only get that with a physical connection, by playing it. I rarely play a whole tune or even a whole chorus that way, but I'll put it lightly on 1 and 3 at slower tempos, or at certain points emphasizing a heavier groove. And I have some other ways of approaching it in a more modern and open way.

For example:

Alan Dawson's Syncopation long note exerciseThis is a Reed interpretation in which you play the short notes (untied 8th notes) on the snare, and the long notes (tied 8ths, quarters, and dotted quarters) on the bass drum, while keeping time with the cymbal and hihat. The way the exercises are written, you'll end up playing a lot of quarter notes on the bass drum, giving your time a nice grounded feeling, while never getting into full-on 1938 groove. For someone like me who was always trying to “hiply” emphasize the &s- this was a big change in direction.

If you're not familiar with it, here's a line of exercise from the book:

Here's how that would be played, with jazz time on the cymbal and hihat added:

Suggesting a funk feelOften a half time feel with the snare drum on three. This can be done explicitly, but I try to be subtle and non-repetitive about it, so it doesn't actually sound like a feel change, or like a funk drummer trying to play jazz:

Quasi-second line feel

In which the bass and snare split a running syncopated line:

The emphasis is on the quasi with that example— that's much more partido alto than second line. The result of writing it too quickly. But you get the picture.

Brushes... fast... hoo...

As I finish up the thing I'm working on, do yourself a favor and visit The Melodic Drummer for an excellent post on playing brushes at really, really fast tempos. You can also brush up (gah!) on your Kenny Washington with his profile at the Jazz Profiles blog- I'll be with you in a moment.

Thursday, January 05, 2012

DBMITW: The Beta Band

Let's feature somebody with an actual video for once:

A few more after the break:

A few more after the break:

Wednesday, January 04, 2012

Transcription: one hour with Live Evil

This morning I sat down with one of my favorite pieces of music- Sivad, from Miles Davis' Live Evil, with Jack Dejohnette on drums- to see what I could do with it in a reasonable amount of time. Fourteen measures in sixty minutes, it turns out. The stopping place is arbitrary- there are four more hell-of-notes measures until the horn comes in, and I knew it would take me another half hour to get them, so I figured that was enough for one post.

You can make the opening little crescendoing half note roll plus swing 16th on the BD yourself. Play the drags as 32nd note doubles. The 32nd sixtuplets appears to be doubles, and most of the remaining 32nd notes are likely singles. I think. Do what works best for you.

I've been playing with Charlie Perry's Beyond the Rockin' Bass book recently, and it reminds me a lot of Dejohnette's funky playing on this record- it's a lot of fun to work with.

Get the pdf

You can make the opening little crescendoing half note roll plus swing 16th on the BD yourself. Play the drags as 32nd note doubles. The 32nd sixtuplets appears to be doubles, and most of the remaining 32nd notes are likely singles. I think. Do what works best for you.

I've been playing with Charlie Perry's Beyond the Rockin' Bass book recently, and it reminds me a lot of Dejohnette's funky playing on this record- it's a lot of fun to work with.

Get the pdf

Monday, January 02, 2012

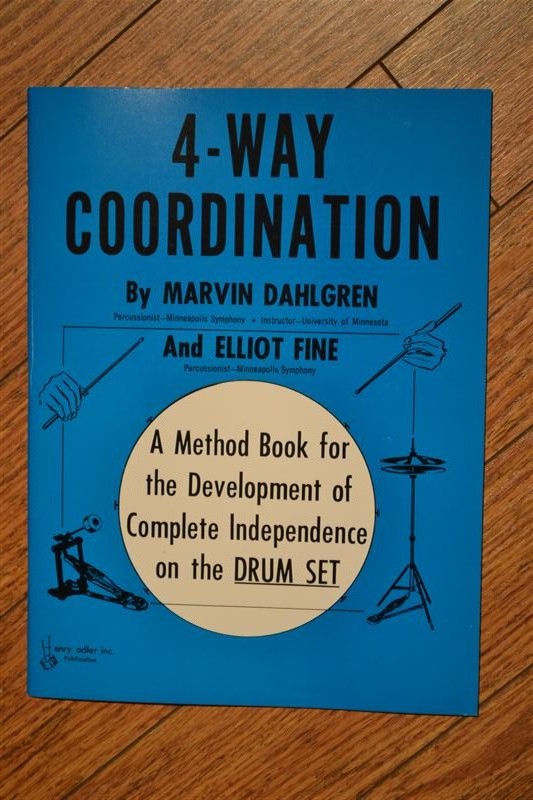

Dahlgren & Fine and me

4-Way Coordination by Dahlgren & Fine is a major piece of drumming literature that I've always had a lot of problems using. There's been a lot of discussion about it on the Drummerworld forum lately, so I've been trying to get to the bottom of my reservations about it. If you don't own it (and you should), you can peruse it online here.

Published in 1963, this is the first book I am aware of to attempt to isolate the problem of independence at the drumset. It opens with the abstract "melodic" and "harmonic" coordination sections (pp. 3-26), which could be described as the the first section of Stick Control applied to four limbs. As written they're very nearly style-free; they feel pretty remote from linear drumming as you encounter it in fusion, modern funk or jazz. I treat them as conditioning exercises, a la Stick Control, or as jumping-off points for developing into something usable. I've had friends disappear down the rabbit hole with this section, with the idea of really getting their fundamentals together once and for all, free of any stylistic baggage; for me there's too little musical hook to spend a lot of time with it. It's too thin.

The last section of jazz exercises ("Four-way coordination on the Drum Set", pp. 27-53) is a much more diluted form of the concept, and is for me the most useful part of the book. It still should be approached with caution; I treat these more as idiomatic conditioners rather than as performance vocabulary. That is, they're jazz-style technical exercises, but are not written/organized in a way that they're easy to recall and play in a musical way in performance. They're good for putting things in your muscle memory, but as presented they don't connect well with actual music. For that you need a different method.

The structure of this section is unique, allowing you to put the patterns in a number of different meters. Each section of pp. 33-48 consists of a base ostinato plus six lines of variations. Each line consists of two 2/4 measures and two 3/4 measures, labeled A, B, C, and D, which you can combine to make measures of 4/4, 5/4, 6/4, and 7/4. I think it's most constructive to practice each measure individually for all sections- that is, play the A measures only for sections 1-22, then the B measures, and so on.

In general, I'm not wild about the premise of the book, which treats a drum part as four independent, equal voices. It can be good practice, but it's fundamentally different from the way jazz drumming is normally conceived. In real playing there are "leader" notes and "follower" notes; important notes and filler.

Contrast that with system based on Ted Reed's Syncopation, which derives any number of complex four-limb drum set parts from a single, relatively simple melodic line. This is fundamental to jazz drumming; basing a drum part off of a written melodic part- a lead sheet, lead trumpet part, big band chart, or sung/heard tune. So the value here for me is more in the way of filling the coordination gaps, of getting under your hands things that don't come up in the usual methods.

4-Way Coordination is a classic book that belongs in every drummer's library, but it fulfills a very narrow purpose.

Published in 1963, this is the first book I am aware of to attempt to isolate the problem of independence at the drumset. It opens with the abstract "melodic" and "harmonic" coordination sections (pp. 3-26), which could be described as the the first section of Stick Control applied to four limbs. As written they're very nearly style-free; they feel pretty remote from linear drumming as you encounter it in fusion, modern funk or jazz. I treat them as conditioning exercises, a la Stick Control, or as jumping-off points for developing into something usable. I've had friends disappear down the rabbit hole with this section, with the idea of really getting their fundamentals together once and for all, free of any stylistic baggage; for me there's too little musical hook to spend a lot of time with it. It's too thin.

The last section of jazz exercises ("Four-way coordination on the Drum Set", pp. 27-53) is a much more diluted form of the concept, and is for me the most useful part of the book. It still should be approached with caution; I treat these more as idiomatic conditioners rather than as performance vocabulary. That is, they're jazz-style technical exercises, but are not written/organized in a way that they're easy to recall and play in a musical way in performance. They're good for putting things in your muscle memory, but as presented they don't connect well with actual music. For that you need a different method.

The structure of this section is unique, allowing you to put the patterns in a number of different meters. Each section of pp. 33-48 consists of a base ostinato plus six lines of variations. Each line consists of two 2/4 measures and two 3/4 measures, labeled A, B, C, and D, which you can combine to make measures of 4/4, 5/4, 6/4, and 7/4. I think it's most constructive to practice each measure individually for all sections- that is, play the A measures only for sections 1-22, then the B measures, and so on.

In general, I'm not wild about the premise of the book, which treats a drum part as four independent, equal voices. It can be good practice, but it's fundamentally different from the way jazz drumming is normally conceived. In real playing there are "leader" notes and "follower" notes; important notes and filler.

Contrast that with system based on Ted Reed's Syncopation, which derives any number of complex four-limb drum set parts from a single, relatively simple melodic line. This is fundamental to jazz drumming; basing a drum part off of a written melodic part- a lead sheet, lead trumpet part, big band chart, or sung/heard tune. So the value here for me is more in the way of filling the coordination gaps, of getting under your hands things that don't come up in the usual methods.

4-Way Coordination is a classic book that belongs in every drummer's library, but it fulfills a very narrow purpose.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)