Continuing with this nerdly topic of problems with roll notation in Charley Wilcoxon's book Rolling In Rhythm; it should have been the authoritative book on rudimental rolls, but is compromised at times by some very sketchy, archaic notation. Last time we looked at 11-stroke rolls on p. 24, until I got tired of it. Today we'll do the 10-stroke rolls on pp. 25-26. Also check out my old post on 7-stroke roll notation in Wilcoxon.

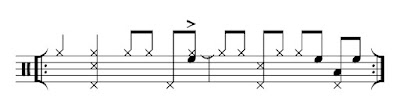

Here's the 10 stroke roll in “triplet” / compound meter form. That's it's native form, probably most familiar to everyone as it occurs throughout the rudimental piece Three Camps:

And here it is in 3/4:

I'm going to try to find literal interpretations of the following notational weirdness, but most likely, those are the intended forms for all of them— maybe in double time, or in a different time signature, but with the same rhythmic structure. The barely-literate rudimental drummer attitude about notation basically goes ehh just fit a 10 stroke roll into this space. The 1s need to be in the right spot, and that's about it.

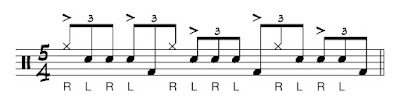

So let's blast off into la-la land, with the next thing on the page:

With that second ruff of each measure, the book repeats the most problematic thing we saw last time; I believe the double is meant to fall on the beat, and the main note (the last 8th note in the measure) is played a 16th note later than it's notated, like this:

Thus violating the modern universal rule of ruff notation, which is to play the main rhythm precisely, and add the ruff strokes to it— the ruff strokes will fall before the beat, and are usually unmetered. Or course there's no way to squeeze that ruff stroke in between the written 32nd notes and the following 8th note.

On the next line on the page we have this:

If that were meant to be played the same as the previous example, it would be a real atrocity— there's not even the ruff notation as a cue that that last 8th note should be played late. Without any other context, I might guess that this was meant to be played with a 16th note triplet pulsation. We see a lot of 8th note length 7-stroke rolls in these studies— this would simply be that, with an extra double at the beginning:

But that would be too fast for the indicated tempo, and there are no other studies using that interpretation— I only suggest it because I'm futilely trying to find a precise interpretation of the notation.

This also illustrates the ass-backwards (and tempo-dependent) nature of rudimental writing in general. Normally, a musical part indicates a roll, and the performing drummer decides what type of roll should be used, based on the tempo, and other musical considerations, to get the best quality roll. Writing into a part ok, monkey, now roll super fast is peculiar to rudimental writers.

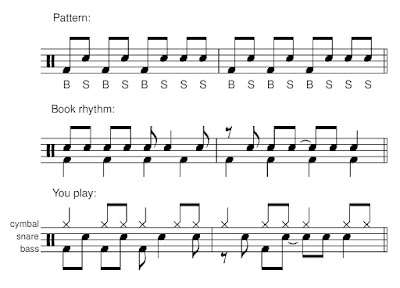

Now look at this:

Lots to unpack there. The “open” 10 is played as 16th notes and ends on beat 4; the “closed” 10 ends on beat 3, so we'll have to play it faster to fit it in. They're using the archaic definitions of open and closed to simply mean slow and fast. In my training, open meant double strokes, and closed meant multiple-bounce strokes— those are the modern meanings of the terms, around here.

The closed example is a complete mess. First, it violates the note values big time— here is that measure of music without the roll:

But if you look at the way the roll stokes line up with the bass drum part, the roll begins

before beat 2, right in the middle of that dotted quarter note. Going by the previous interpretations, you could play that either of these ways— as 16th notes with that 8th note played late:

...or as 16th note triplets, with the 8th note played as written:

Either of those interpretations put an unnaturally large space between that opening accent and the roll itself, which, again, we don't see anywhere else. Normally with a 10-stroke roll, we expect the starting and ending accents to be at the same pulsation speed as the body of the roll, like in the first two examples.

And of course playing either of those interpretations at half note = 96 doesn't work at all. So probably what's actually intended is to just play this, or something close to it:

Clearly we have to relax our modern standards for precision with some of this stuff. Hit the 1 and 3 accurately and get the right number of notes and you're golden. That's close enough, apparently. In fact, these posts seem to have been a very long winded way of saying “traditional rudimental notation was shamefully imprecise, slovenly, and often misleading.”