The following are some comments I made in a contentious online conversation about snare drum training and drum set training— or playing— and the differences between the two, that I think stand on their own— edited slightly for clarity:

The snare drum and the drum set are different instruments, played differently.

Snare drum training is two handed playing on one drum, dealing with all areas of performance on the snare drum— reading, accents, flams and ruffs, rolls, rudiments. See any method book, technique book, and rudimental book: Podemski, Goldenberg, Stone, Wilcoxon. Intermediate Snare Drum Studies and Rudimental Primer by Mitchell Peters give a reasonable minimum standard for baseline proficiency.

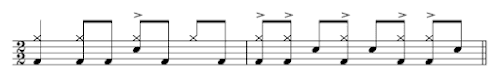

Drum set training means playing the drum set, a four limbed instrument using a snare drum, a bass drum, some cymbals, and some tom toms, as a coordinated thing. Training involves things related to coordination, styles, the functions of the components of the instrument, playing and setting up figures, reading interpretively, improvising, filling, soloing.

Much of that we develop through the book Syncopation— the most common things done with it are in John Ramsay's Alan Dawson book. I've also written a hundred or so systems for it on my site. Other books broadly outlining that are Steve Houghton's Studio and Big Band Drumming book, Ed Uribe's Brazilian and Afro-Cuban books, and Kim Plainfield's Advanced Concepts book. Those all outline the primary techniques of the instrument, and practice systems for developing them.

You can't get where those books take you just by getting good with your ratamacues.

Much of ordinary drum set playing doesn't require a lot of technical ability as a snare drummer. Though it can be very helpful, and necessary for some ways of playing. And necessary if someone's going to be a competent professional.

The drum set has its own language now. Approaching the drum set as “snare drumming plus some other stuff” is antiquated.

Reading real old drumming materials it's kind of shocking how contemporary some of it is. And how not. Much of it is oriented around how to play a 2/4 march and how to play a 6/8 march, and that's about it. 2 feel with the bass drum / 4 feel with the bass drum.

On the snare drum alone, I don't see a great logic to playing patterns 1-72 in Stick Control, except it's a different sequence of Rs and Ls. The sequences themselves are an important part of the language of drumming, but I don't know how helpful it truly is to just learn a lot of ways of making static 8th notes on one drum. Except to work on evenness between hands— which is something, but not everything.

It's kind of like making a piano student run their scales with all the notes on the keyboard sounding middle C. The differences in pitches aid understanding the thing, they're the whole reason for the thing.

I don't know of another instrument that requires people to learn complex fingerings while sounding a single pitch.

I learned most of Stone on an actual snare drum, standing up in a little hallway at school— an hour of Stone like that. Flam pages 21-23. It was a miserable way to practice, and ultimately poor practice economy for the effort.

If you play 1-72 from Stone on a drum set with the hands hitting two different sounds, there's an obvious musical difference between the patterns— there is a reason to play one over another, an auditory difference. So you learn the pattern as a piece of musical content, not just as a mathematical sequence.

Part of why so many drummers are such lousy musicians is they think in terms of Rs and Ls and not in terms of melodic ideas— which we get from that latter thing.

The bigger reason to do a lot of snare drum is not just for how you'll use it directly. Your hands are still where most of your facility is going to be. There are some bodies of SD materials that are pretty essential to more-than-basic drum set playing— accented singles, flam rudiments, paradiddle rudiments, open rolls and drags. And the more advanced snare drum materials cover some things that no drum set materials cover— finer aspects of rhythm, various forms of time changes, finer dynamic control, and timing control.

Different students have different goals. We start on snare drum, and continue with it as necessary, as their goals evolve. The two instruments develop concurrently.

I teach all levels of people, with all sorts of playing goals that are not mine. Not everyone knows how serious they're going to be about it when they start. Many of them are not irrationally motivated to do it, as I was, and need to be given a chance to get hooked, and get more ambitious about what they want to accomplish with it.

The idea is not to teach limitation, the idea is to find a path forward for everyone, and teach things in a timely manner with the growth of their interest, goals, and commitment.

I get a lot of students who were poorly taught— by themselves, or others. There are a lot of very bad drum teachers (and bad drummers) out there, often teaching ideas they inherited from their teacher, that they never really understood, and never questioned. Or they try to reinvent the instrument based on some popular trends, without understanding what they're reinventing. I'm not thrilled with the way a lot of people do things on this instrument. There are a lot of lingering primitive ideas about how it works.

Nothing half assed about any of this— I put a tremendous amount of energy into helping my students become excellent and creative players to whatever extent they want to pursue it.

How much snare drum would you require before touching a drum set for a nine year old beginner? Or a 70 year old beginner? Or someone with a high pressure job who does music as a distraction from that?

Also see this post on snare drummers vs. drum set players.