To celebrate Devo drummer Alan Myers, who just died, here's a transcription of Clockout, from the band's Duty Now For The Future album.

There are some non-significant variations that happen on each repeat— just play, and don't sweat them. Note that the number of measures you play the 16th notes a the end of the form varies; the bass entrance cues the last six beats before the repeat. Don't miss the fine.

Get the pdf.

Audio after the break:

Sunday, June 30, 2013

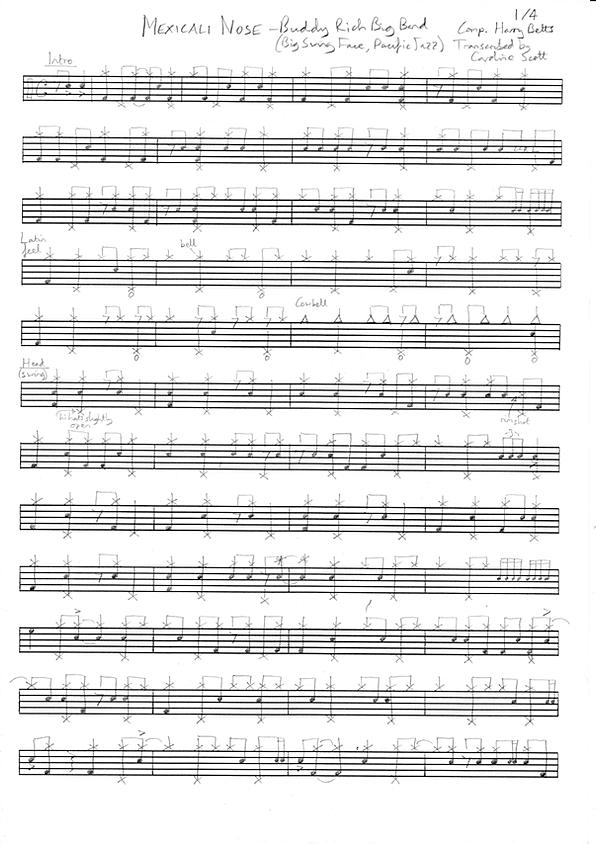

Three Buddy Rich transcriptions

London-based drummer Caroline Scott has posted three Buddy Rich transcriptions— Big Swing Face, Mexicali Nose, and Love For Sale— sort of the big three of Buddy tunes for me, plus Ya Gotta Try. Very worth grabbing.

Visit her site to get the pages, plus some other things— a Brian Blade transcription, and more.

Audio of the tunes after the break:

Visit her site to get the pages, plus some other things— a Brian Blade transcription, and more.

Audio of the tunes after the break:

Thursday, June 27, 2013

Groove o' the day: Freddie Waits — African Village

Here's another afro 6 alternative— we haven't had any new ones lately. Played by Freddie Waits, on the tune African Village on McCoy Tyner's Time For Tyner, released in 1968:

I've written this in a fast 6/4, phrased as 6/8+3/4. The hihat on beats 2 and 5 pulls it into the jazz waltz, ah, “domain”; putting it on a dotted quarter note rhythm would give it more of an African feel— I suggest learning it that way as well. Or you can do as Waits does during parts of the solos (especially after 5:00) and put the bass drum on the dotted quarters; when he does that he generally plays the cymbal pattern from the first half of the measure only— the 6/8 part. You'll hear it.

Audio after the break:

I've written this in a fast 6/4, phrased as 6/8+3/4. The hihat on beats 2 and 5 pulls it into the jazz waltz, ah, “domain”; putting it on a dotted quarter note rhythm would give it more of an African feel— I suggest learning it that way as well. Or you can do as Waits does during parts of the solos (especially after 5:00) and put the bass drum on the dotted quarters; when he does that he generally plays the cymbal pattern from the first half of the measure only— the 6/8 part. You'll hear it.

Audio after the break:

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Perspectives on cymbals, part the first

You may have noticed that I've lately been advocating for heavier cymbals than are currently in fashion, especially among jazz drummers. After pursuing ever lighter cymbals for most of the oughts, finally settling on some thin Bosphorus Turks and Master series cymbals, I began to sense that they weren't projecting much beyond the edge of the stage, and that they were doing something funny to the balance of the ensemble— they seemed to induce a kind of death spiral of softness, with everyone trying to play down to the level of the cymbals, and me playing quieter to stay under the band, who then try to play quieter still. Traditional medium-weight cymbals, or heavier ones like my 22" Paiste behemoth— even when played very softly— have more presence, and seem to free the other players to play with a bigger, more natural sound.

I say frees because, despite people's sensitivity about cymbals, and volume in general, I think few musicians truly want to do all of their playing within the bottom 10% of their dynamic range, and listening audiences want the band to be loud enough to not be obliterated by the waitress setting down some drinks at the next table.

For different reasons, I've also been letting in some drier cymbals, which runs a little bit counter to the above thing. Unmiked, they don't necessarily project well to the audience, but at times I felt that the band was hearing the pulse as a wide sound, and losing it a little bit, and I wanted to narrow down the attack for them. The dry cymbals (a 602 flat, and an older Dejohnette signature Sabian) seem to have a sonic envelope more like a drum, which gives you almost the feeling of being a conga drummer— with the entire instrument having the same decay— which encourages me to play a little differently.

Anyhow, coming up we'll have a few posts here kicking around issues with cymbals. First, coming from strictly a jazz perspective, there's this video “Balancing Your Sounds” by Ian Froman, from the Vic Firth site. VF doesn't allow embedding, so you'll have to go there and view it. He generally advocates playing other parts of the instrument softer than the ride cymbal— or rather, hitting them softer than the ride to avoid overwhelming it.

Actually, someone has put the video on YouTube unofficially— if it gets taken down, hit the link above to view it at the VF site:

He's identifying the principle behind something you should already be doing if you're listening to what you're playing, rather than just playing based on what feels good muscularly. And because I know how drum students think: you do not need to revamp your technique, “baking in” the uneven stick heights. Instead, listen to the sound you're making, and use Froman's principle as a guide for correcting your balance.

More coming...

I say frees because, despite people's sensitivity about cymbals, and volume in general, I think few musicians truly want to do all of their playing within the bottom 10% of their dynamic range, and listening audiences want the band to be loud enough to not be obliterated by the waitress setting down some drinks at the next table.

For different reasons, I've also been letting in some drier cymbals, which runs a little bit counter to the above thing. Unmiked, they don't necessarily project well to the audience, but at times I felt that the band was hearing the pulse as a wide sound, and losing it a little bit, and I wanted to narrow down the attack for them. The dry cymbals (a 602 flat, and an older Dejohnette signature Sabian) seem to have a sonic envelope more like a drum, which gives you almost the feeling of being a conga drummer— with the entire instrument having the same decay— which encourages me to play a little differently.

Anyhow, coming up we'll have a few posts here kicking around issues with cymbals. First, coming from strictly a jazz perspective, there's this video “Balancing Your Sounds” by Ian Froman, from the Vic Firth site. VF doesn't allow embedding, so you'll have to go there and view it. He generally advocates playing other parts of the instrument softer than the ride cymbal— or rather, hitting them softer than the ride to avoid overwhelming it.

Actually, someone has put the video on YouTube unofficially— if it gets taken down, hit the link above to view it at the VF site:

He's identifying the principle behind something you should already be doing if you're listening to what you're playing, rather than just playing based on what feels good muscularly. And because I know how drum students think: you do not need to revamp your technique, “baking in” the uneven stick heights. Instead, listen to the sound you're making, and use Froman's principle as a guide for correcting your balance.

More coming...

Tuesday, June 25, 2013

Alan Myers 1955-2013

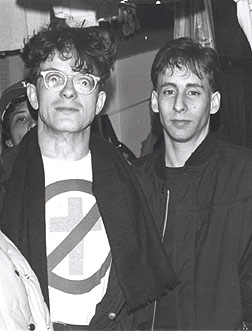

|

| Mark Mothersbaugh and Alan Myers, way back when. |

UPDATE: A notice on the Modern Drummer site.

After the break there are a few live clips from Devo's early days.

Page o' coordination: 5/8 + 5/8 — 02

More fun with 5/4, gateway to all odd meters. I guess. Getting it together does seem to make the others quite a bit easier. This is our second entry using the 5/8+5/8 construction:

When getting the ostinatos together, don't try to swing the first one, written in 5/8, and do swing the second, written in 5/4. Though this was written to be played with swing 8ths, you can also play them straight; when doing that, you can push the triplets around to make 16th note rhythms, usually “1 e &”. So this exercise:

Would be played like this:

Don't let the typo in the hihat part throw you, there. For variety, you could also play beat 1 like this:

Use this and the other “pages o'” as workouts, playing each exercise at least 4-8 times, continuing to the next one without stopping. Doing the tom moves can extend this considerably, depending on how thorough you want to be with them— it's worth the extra time to do that.

Get the pdf

When getting the ostinatos together, don't try to swing the first one, written in 5/8, and do swing the second, written in 5/4. Though this was written to be played with swing 8ths, you can also play them straight; when doing that, you can push the triplets around to make 16th note rhythms, usually “1 e &”. So this exercise:

Would be played like this:

Don't let the typo in the hihat part throw you, there. For variety, you could also play beat 1 like this:

Use this and the other “pages o'” as workouts, playing each exercise at least 4-8 times, continuing to the next one without stopping. Doing the tom moves can extend this considerably, depending on how thorough you want to be with them— it's worth the extra time to do that.

Get the pdf

Saturday, June 22, 2013

Podcast — Episode 6: Todd's playalong tracks

Hey, we haven't done a podcast in some time, have we? I've been doing most of my drumset practicing along with recordings recently— book exercises and everything— and I thought I'd share some of the things I've been using, along with a few notes about them. You'll probably want to download the mp3, and cut it up into individual tracks using Audacity, or whatever, and then load them onto your mp3 player.

You can just play along with these normally in the style of the tune, but I also recommend using them for your technical/book stuff; hearing those materials in context will help you move them into your regular playing. You can also play along in any style you want, if it sort-of fits— most often I'll play stuff from funk or rock books along with Brazilian recordings— hopefully it will give you a little bit of a different take both on how you play the style of the recording, and the style you are playing “against” it.

You can listen on the embedded player, or at the podomatic site, or you can download the mp3:

Here's a list of the tracks, with some notes on them:

Funkadelic — Can You Get To That

I've been doing two major things with this: pp. 11-22 of the Burns/Farris funk book, and the “harmonic” coordination section of Dahlgren & Fine. You can also just learn the actual groove from the recording.

Nara Leão — Nanã

I used this when I was first starting to crack that section of Dahlgren & Fine because I like the song, and the tempo is nice and relaxed.

Milton Banana — Linha De Passe

A nice bright samba. You should notice a big difference in feel between playing with this vs. a group of American jazz musicians playing a similar-tempo samba; the authentic rhythms make more sense— and are pretty much unavoidable— when playing with recordings of Brazilian musicians. Try using my page of Brazilian rhythms, playing both hands in unison on the cymbal and snare, over the samba BD/HH ostinato.

Milton Banana — Acquarela

A modern baiao type of feel, with a samba on the B section. I've been using this to work on my baiao, but you could play any funk material along with this. I think in general people overplay their funk stuff, and this will give you an avenue for lightening your touch.

Batacumbele — Se Le Fue

I've been using this to work on my songo, with the workout from Ed Uribe's Essence of Afro-Cuban Percussion and Drum Set. If you don't have that, or another good book, you could use my songo page o' coordination. Clave is 2/3 son, and is consistent all the way through the piece.

Eddie Palmieri — Vamanos Pal'Monte

Mambo— maybe someone with better knowledge of salsa songstyles than me can give a more precise ID of the style. There's a tempo change towards the end, which will give you a little test on the material you played through during the first part. I've been using the mambo workout from Uribe's book, but any mambo, Latin jazz, or cascara materials you have should work with it. Clave is, again, 2/3 son.

Continued after the break:

You can just play along with these normally in the style of the tune, but I also recommend using them for your technical/book stuff; hearing those materials in context will help you move them into your regular playing. You can also play along in any style you want, if it sort-of fits— most often I'll play stuff from funk or rock books along with Brazilian recordings— hopefully it will give you a little bit of a different take both on how you play the style of the recording, and the style you are playing “against” it.

You can listen on the embedded player, or at the podomatic site, or you can download the mp3:

Here's a list of the tracks, with some notes on them:

Funkadelic — Can You Get To That

I've been doing two major things with this: pp. 11-22 of the Burns/Farris funk book, and the “harmonic” coordination section of Dahlgren & Fine. You can also just learn the actual groove from the recording.

Nara Leão — Nanã

I used this when I was first starting to crack that section of Dahlgren & Fine because I like the song, and the tempo is nice and relaxed.

Milton Banana — Linha De Passe

A nice bright samba. You should notice a big difference in feel between playing with this vs. a group of American jazz musicians playing a similar-tempo samba; the authentic rhythms make more sense— and are pretty much unavoidable— when playing with recordings of Brazilian musicians. Try using my page of Brazilian rhythms, playing both hands in unison on the cymbal and snare, over the samba BD/HH ostinato.

Milton Banana — Acquarela

A modern baiao type of feel, with a samba on the B section. I've been using this to work on my baiao, but you could play any funk material along with this. I think in general people overplay their funk stuff, and this will give you an avenue for lightening your touch.

Batacumbele — Se Le Fue

I've been using this to work on my songo, with the workout from Ed Uribe's Essence of Afro-Cuban Percussion and Drum Set. If you don't have that, or another good book, you could use my songo page o' coordination. Clave is 2/3 son, and is consistent all the way through the piece.

Eddie Palmieri — Vamanos Pal'Monte

Mambo— maybe someone with better knowledge of salsa songstyles than me can give a more precise ID of the style. There's a tempo change towards the end, which will give you a little test on the material you played through during the first part. I've been using the mambo workout from Uribe's book, but any mambo, Latin jazz, or cascara materials you have should work with it. Clave is, again, 2/3 son.

Continued after the break:

Friday, June 21, 2013

VOQOTD: on swinging

To me, any drummer who hits the drums too hard doesn’t swing.

— Peter Erskine

Read the entire Drum! Magazine interview from 2000.

— Peter Erskine

Read the entire Drum! Magazine interview from 2000.

Thursday, June 20, 2013

A page of Brazilian rhythms

Here I've pulled the snare drum parts from a random selection of bossa nova/samba records— by Baden Powell, Tamba Trio, Milton Banana, and others. Some of these are played fairly repetitively on the recording, some are variations, and played only once. A few of them were played on tamborim, the instrument the commonly-played rim clicks on the snare drum are meant to emulate.

Along with the ostinatos I've given (or a Baião foot pattern), play these rhythms on the snare drum, either as rim clicks, or normally on the drum, while varying the accents/articulation— using rim shots, buzzes, ghosting some notes, or whatever. Once you have the patterns together improvise variations on them— alternate playing the given pattern one time with an improvised variation on it. And play them along with recordings featuring actual Brazilian musicians, not American jazz musicians playing bossa nova style— you'll find that with the Brazilians, the entire ensemble derives their parts from these types of rhythms, and you will fall right into a groove with them.

Get the pdf

Along with the ostinatos I've given (or a Baião foot pattern), play these rhythms on the snare drum, either as rim clicks, or normally on the drum, while varying the accents/articulation— using rim shots, buzzes, ghosting some notes, or whatever. Once you have the patterns together improvise variations on them— alternate playing the given pattern one time with an improvised variation on it. And play them along with recordings featuring actual Brazilian musicians, not American jazz musicians playing bossa nova style— you'll find that with the Brazilians, the entire ensemble derives their parts from these types of rhythms, and you will fall right into a groove with them.

Get the pdf

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

Two links

|

| Hit the link for the full-size scans. |

Also at the link is a recent video of a Terry Bozzio playing the piece, which will come in handy if you want to actually learn it.

Second, a new addition to our blogroll— a fan site dedicated to Jim Keltner, including his complete discography, with album personnel and notes, photos, and, most interestingly, scans of a lot of rare print interviews. I'll be linking to a lot more from this site.

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

Northern Brazilian drumming

From the Vic Firth site, here's a nice clinic on northeastern Brazilian drumming, by US drummer Scott Kettner. He discusses the folkloric/authentic forms of the Baião and Maracatu rhythms, which have a history of being adapted for the drumset outside of Brazil, and also Forró (pronounced fo-HO) rhythms, which doesn't so much, but we're starting to hear more about it— I know of at least one good Forró

group in Portland, for example.

This clip starts with a clarification on what how Baião— which should be familiar to most people reading this at least as a type of drumset groove— is actually played in Brazil, raising a point about authenticity which I'll continue below.

This is welcome information, because it's certainly better to be educated about what we're doing than to be ignorant about it, but at the same time, our familiar Baião-influenced groove has its own history of usage by some great musicians outside of its original location and context, and is an artistically viable derivation in its own right. And just as a practical matter, when American musicians call for the style, the musical setting will very likely have little in common with the real thing as practiced in Brazil, or anywhere else, and it's going to be some form of that familiar drumset adaptation they'll be expecting to hear. Though you would have the option of educating them about what the authentic groove is if you know it.

Anyhow, the entire clinic is well worth watching— there's also downloadable a nice fat clinic handout which I would be sure to grab.

This clip starts with a clarification on what how Baião— which should be familiar to most people reading this at least as a type of drumset groove— is actually played in Brazil, raising a point about authenticity which I'll continue below.

This is welcome information, because it's certainly better to be educated about what we're doing than to be ignorant about it, but at the same time, our familiar Baião-influenced groove has its own history of usage by some great musicians outside of its original location and context, and is an artistically viable derivation in its own right. And just as a practical matter, when American musicians call for the style, the musical setting will very likely have little in common with the real thing as practiced in Brazil, or anywhere else, and it's going to be some form of that familiar drumset adaptation they'll be expecting to hear. Though you would have the option of educating them about what the authentic groove is if you know it.

Anyhow, the entire clinic is well worth watching— there's also downloadable a nice fat clinic handout which I would be sure to grab.

Monday, June 17, 2013

Groove o' the day: Robertino Silva — Saídas E Bandeiras

Been having a little bit of writer's block in finishing several longer pieces this week, so let's do something easy. Here's a simple rock beat in 5/4 by one of my favorite Brazilian drummers, Robertinho Silva, on Saídas E Bandeiras (No. 1 or 2— there are two versions on the record) on Milton Nascimento's great Clube da Esquina album:

I left off the key, but you can figure it out: top line = hihat, middle line = snare, bottom = bass. In the No. 2 version he develops the groove a little bit on the instrumental section, emphasizing quarter note pulse on the hihat, and the &s on the bass drum, playing the snare on the 5-&, and making some other variations.

Audio of the track after the break, plus, for comparison, a couple of covers of the song with busier drumming:

I left off the key, but you can figure it out: top line = hihat, middle line = snare, bottom = bass. In the No. 2 version he develops the groove a little bit on the instrumental section, emphasizing quarter note pulse on the hihat, and the &s on the bass drum, playing the snare on the 5-&, and making some other variations.

Audio of the track after the break, plus, for comparison, a couple of covers of the song with busier drumming:

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

Groove o' the day: more Al Jackson

This one goes out to my man Ed Pierce; I've really been getting into the Al Jackson this week. Here's most of what he plays on Soul Jam, by Booker T. and the MGs, from their And Now! album:

Oh, what the heck, let's do the whole thing. This may look like a chart, but it's an exact transcription of everything Jackson plays on the record:

How do you build intensity without embellishing, changing parts, or significantly changing dynamics? It takes a lot of confidence, and trust in the music and the other musicians to play this minimally; there's really nothing here except the groove, a stop, a few punctuations, and a little set up for the ending vamp.

I've broken from convention and notated literally the swing rhythm on the vamp at the end— the jazz way of indicating swing 8ths doesn't seem entirely appropriate for R&B. I've used a dotted-8th/16th rhythm because he plays it a little closer to that feel than straight triplets, as you'll hear— Jackson's swing on the vamp is slightly more staccato than that of the rest of the band. But also note that the “skip” note on the bass drum is always solo; that note never lands in unison with any of the other parts.

Get the pdf

Audio after the break:

Oh, what the heck, let's do the whole thing. This may look like a chart, but it's an exact transcription of everything Jackson plays on the record:

How do you build intensity without embellishing, changing parts, or significantly changing dynamics? It takes a lot of confidence, and trust in the music and the other musicians to play this minimally; there's really nothing here except the groove, a stop, a few punctuations, and a little set up for the ending vamp.

I've broken from convention and notated literally the swing rhythm on the vamp at the end— the jazz way of indicating swing 8ths doesn't seem entirely appropriate for R&B. I've used a dotted-8th/16th rhythm because he plays it a little closer to that feel than straight triplets, as you'll hear— Jackson's swing on the vamp is slightly more staccato than that of the rest of the band. But also note that the “skip” note on the bass drum is always solo; that note never lands in unison with any of the other parts.

Get the pdf

Audio after the break:

Monday, June 10, 2013

Groove o' the day: Al Jackson

Here's something from the great R&B drummer Al Jackson, on the light little instrumental tune Overton Park Sunrise, from the Union Extended album by Booker T. & The MGs. On the A section he plays the ride cymbal, rim clicks on the snare drum, some James-Brownish displacement in the middle, and the same little fill every two measures:

On the B section he switches to a more straight ahead rock beat, played on the hihat, with backbeats on the snare drum:

As always, Jackson is an architect, and his playing is clean in the extreme. Everything serves a compositional purpose, and nothing happens by accident. He doesn't play hard or loud. Fills are sparse until the out chorus, when he catches a hit on the & of 4 while playing the B groove, which you'll hear. So much of current funk drumming— what gets called funk drumming— is so overwrought that Jackson's sensibility could seem a little alien. Just remember that he became one of the most revered drummers in history doing little more than what you hear on this recording, and try to figure out why that would be.

Audio after the break:

On the B section he switches to a more straight ahead rock beat, played on the hihat, with backbeats on the snare drum:

As always, Jackson is an architect, and his playing is clean in the extreme. Everything serves a compositional purpose, and nothing happens by accident. He doesn't play hard or loud. Fills are sparse until the out chorus, when he catches a hit on the & of 4 while playing the B groove, which you'll hear. So much of current funk drumming— what gets called funk drumming— is so overwrought that Jackson's sensibility could seem a little alien. Just remember that he became one of the most revered drummers in history doing little more than what you hear on this recording, and try to figure out why that would be.

Audio after the break:

Friday, June 07, 2013

What is HIP?

George Colligan is trying to create a said thing. At his Jazz Truth blog there's a post highly worth reading, about High Intensity Practicing, or HIP— his phrase— or “practicing REALLY HARD, at a sort of all out intensity, for a short period of time.” Mainly, it seems to involve actually practicing things you can't do. Putting yourself in that space is not easy, because it means persisting and maintaining focus while sounding like— not much; and nobody likes feeling like they're struggling.

A slightly contrary thing that has never been too far from my mind is Peter Erskine's commandment of first be able to play a simple beat really well, which encourages a lot of practicing for refinement as you try to assess whether you are really playing that AC/DC beat truly well, yet. And I've never been so bold as to think I could really do everyday stuff well enough to stop relearning it and polishing it. But learning to play is not a strictly zero sum thing like that, and working on new, hard stuff using a lot of concentration effects your daily material for the better, too.

Anyway, Colligan ends with this quotation, some variation of which has been a big deal to me for years:

We've been talking about doing this in the practice room, but I've always tried to apply it on the stand, too... but that's for another post...

A slightly contrary thing that has never been too far from my mind is Peter Erskine's commandment of first be able to play a simple beat really well, which encourages a lot of practicing for refinement as you try to assess whether you are really playing that AC/DC beat truly well, yet. And I've never been so bold as to think I could really do everyday stuff well enough to stop relearning it and polishing it. But learning to play is not a strictly zero sum thing like that, and working on new, hard stuff using a lot of concentration effects your daily material for the better, too.

Anyway, Colligan ends with this quotation, some variation of which has been a big deal to me for years:

It's fascinating watching the Ken Burns documentary on Jazz and watching Artie Shaw talk about the Glen Miller Band during the Swing Era.

And I didn't like Miller's band, I didn't like what he did. Miller was, he had what you'd call a Republican band. It was, you know, very straight laced, middle of the road. And Miller was that kind of guy, he was a businessman. And he was sort of the Lawrence Welk of jazz. And that's one of the reasons he was so big, people could identify with what he did, they perceived what he was doing. But the biggest problem, his band never made a mistake. And it's one of the things wrong, because if you don't ever make a mistake, you're not trying, you're not playing at the edge of your ability. You're playing safely, within limits, and you know what you can do and it sounds after a while extremely boring.

We've been talking about doing this in the practice room, but I've always tried to apply it on the stand, too... but that's for another post...

Wednesday, June 05, 2013

Drum clinic artifacts

Right now I'm working on a couple of very wordy pieces, and since I view words primarily as vectors for self-embarrassment, it's taking me a long time to finish them. In the mean time, you should check out these posts:

Four On The Floor — Ed Shaughnessy drum clinic handouts

Jon McCaslin has for us several pages from a 1992ish clinic by Shaughnessy. At the left is his handout with his a unique explanation for his unique way of playing the ride cymbal. You sense with these that you're missing a good deal, absent his verbal explanation, but that's OK; I'm in favor of working with partial information.

Bang! The Drum School blog — Philly Joe Jones drum clinic audio

Mark Feldman links to some rare audio from a 1979 clinic by Jones— who was a drummer, not an educator, and the useful information is not instantly digestible. But it's Philly Joe. You have to listen.

Four On The Floor — Ed Shaughnessy drum clinic handouts

Jon McCaslin has for us several pages from a 1992ish clinic by Shaughnessy. At the left is his handout with his a unique explanation for his unique way of playing the ride cymbal. You sense with these that you're missing a good deal, absent his verbal explanation, but that's OK; I'm in favor of working with partial information.

Bang! The Drum School blog — Philly Joe Jones drum clinic audio

Mark Feldman links to some rare audio from a 1979 clinic by Jones— who was a drummer, not an educator, and the useful information is not instantly digestible. But it's Philly Joe. You have to listen.

Tuesday, June 04, 2013

VOQOTD: Max Roach on what it's about

“It’s not about comparative things: who’s the fastest, or… it’s not about that. It’s about someone who, when you hear them, you say, Oh, that’s Tony! Oh, that’s Miles! Ah, that’s John Coltrane! That’s what it’s about.”

— Max Roach

From Jazz Times.

— Max Roach

From Jazz Times.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)