I don't know, I just felt like writing an inane Buzzfeed-style listicle a few weeks ago, and I'm tired of looking at this in my drafts folder. Please don't be offended if one of your favorite things is listed here:

|

| Don't do this. |

Budget/student quality cymbals

I've pointed out many times that old, filthy, pro-quality A. Zildjians and early Sabian AAs

are now dirt cheap. The only excuses for buying student cymbals are embarrassingly horrible: you like the metal to be shiny, you like for all the logos to be the same, or you are a disturbing virginity fetishist, and cannot use products that have been touched by human hands.

Double-bass pedal

Nobody wants to hear that noise, unless you're in a Metal band. Which you should quit if you're in. Go join a Buddhist monastery, find a shaman to lead you in an ayahuasca session, exorcise whatever demons are causing your pain, and learn to love. Especially, learn to love music the sole purpose of which is

not to arouse feelings of intense negativity. It all starts with the pedal. Get rid of the pedal and you break the spell.

And Cruise Ship Drummer! becomes a little more openly anti-Metal...

Third, fourth, fifth tom tom

Once the band is playing, people just hear a high sound and a low sound. This isn't the 70s— nobody is leaving spaces in their arrangements for big melodic tom fills. So let's end this charade.

Special note: Wanted: 13" Sonor Phonic tom tom, or 16" floor tom, black wrap.

10" tom tom

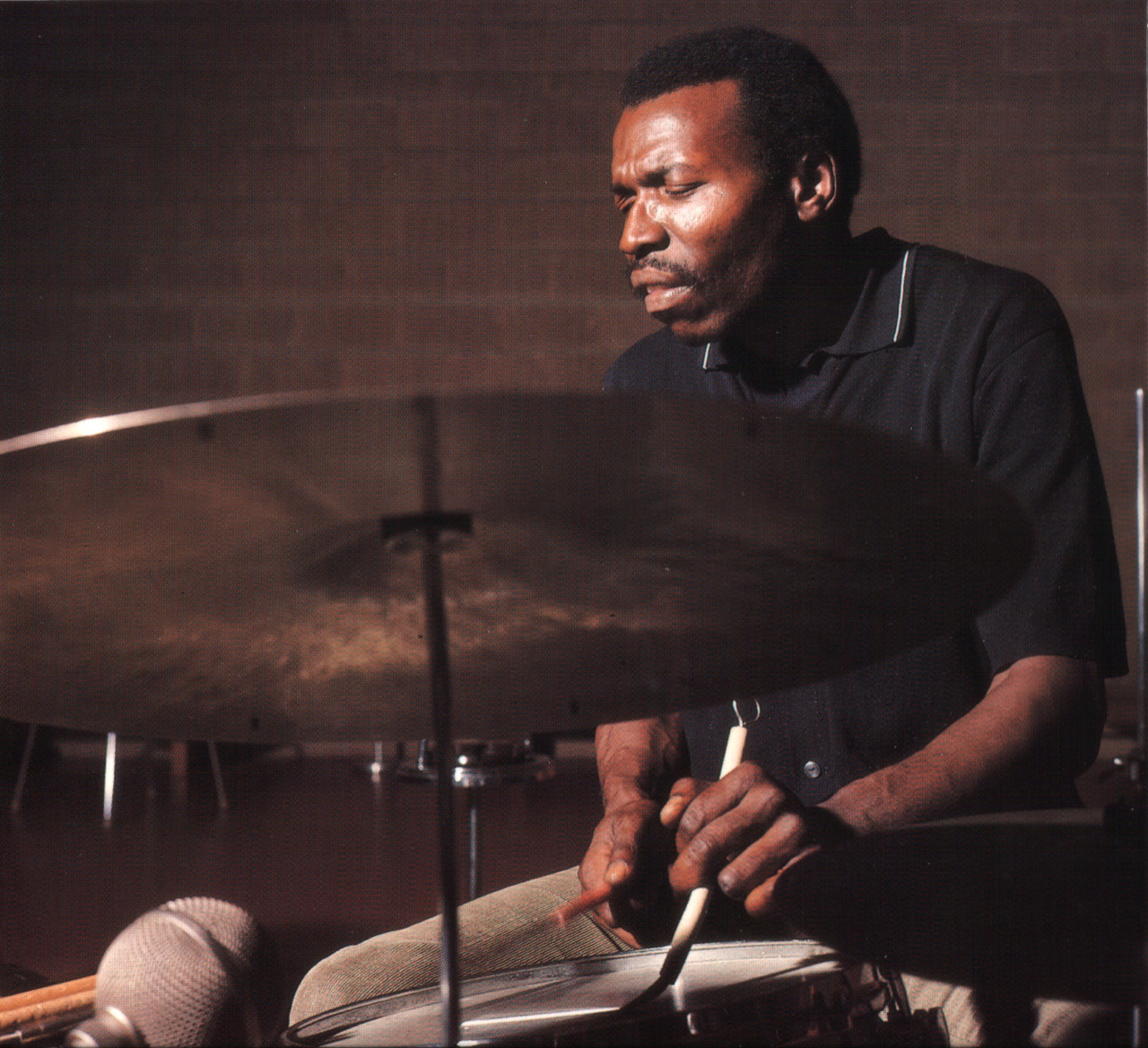

Steve Gadd called, and he wants his personal thing back. Gadd is, of course, wonderful, and his distinctive, punchy little 10" tom tom won everyone's hearts back in the late 70s, but it really is a specialty sound. And the way you set up the drums, the 10 is always right there, so you're always playing this extra-high, bongo sound; and I am not adopting some weird-looking set up just to keep me from playing that drum too much. Just lose the thing.

Special note: Wanted: 10" Sonor Phonic tom tom, black wrap.

|

| See, yeah... no. |

Second, third China-type

It's extremely rare that anyone remarks on the absence of a Chinese cymbal on a gig. So what are you doing with three of them? See the above thing about the double-bass pedal.

Vic Firth SD-4 Combo drum sticks

Every jazz drummer in the world uses these, but for my taste they deliver a thin tone, and they're too short— playing above

mf, they make you wave your arms around, and use more force than I would like. Try larger maple sticks—

you can still play quietly with them. [

2020 UPDATE: my views on smaller sticks

have moderated somewhat since this post. I still don't like the Combos.]

Piccolo or “popcorn” snare drums

The sound of your snare drum should not send your recording engineer lunging to figure out which piece of outboard gear has just begun spewing random digital artifacts. Play a 14". Or a deep 13". And tune it normally. When in doubt, go to your record library, listen to your Police albums, and if your drum sounds significantly higher and lacking-in-substance than Stewart Copeland's, and you are not making a Reggae album,

you are way out of line.

Special note re: piccolos: the year 1990 called, and it wants etc etc...

Special note re: popcorn snares: the year 2005 called, blah blah blah...

Drum rack

What are you still doing with that thing? Racks went out with mullets, wine coolers, and Winger. Call the dump and have them tow away that IROC Z-28 Camaro while you're at it.

Goofy, specialty hardware in general

If it's not covered by the cheapest end of the Yamaha line, you don't need it. With very few exceptions. They don't make a flat base cymbal stand, so, OK, if it's not

also covered by the next-to-cheapest Gibraltar line (their dead-cheapest stuff is real swill), you don't need it. And no building clever things with multi-clamps! What matters is what you're going to play, and how.

|

Just get something

reasonably-priced

that looks like this. |

That goes for extra-ridiculous bass drum pedals, too

Aside from a few new gimmicky things for playing Metal, which you should not own— or play— all pedals are the same today. Two posts, vertical spring on the side, little swinging cam, possibly chain drive? Sometime in the early 90s, everyone just said

eff it, people, we're all going to sell slight variations on the Frank Ippolito/Al Duffy Gretsch Floating Action pedal from the 40s— that's the pedal that became the Camco, which became the DW 5000, and then everything else. For years all companies used a variation of that design for their crappiest pedal, until customers realized that their fancier, proprietary designs

totally ate, and stopped buying them, which led to the great,

late-80s fancy, proprietary bass drum pedal design die-off, after which the only thing left standing was the Floating Action design. Now everything from First Act to Axis uses the same mechanism. Pass on the Axis, or whatever is the boutique pedal du jour, and just buy the cheapest Yamaha pedal.

Bonus for drum corps people: Kevlar heads

They sound like garbage, and have

stolen your balls. Break into the Ludwig warehouse and steal their remaining stock of Silver Dot heads. Tenors, get Remo Pinstripes. You will instantly have triple the power of every other drum line in the world.