Purely exploring an idea that occurred to me during a lesson— this has nothing to do with anything. Except I'm writing a new book about developing the Afro 6 groove, so I'm thinking about the following ideas a lot. And I've noticed, in dealing with Latin rhythms and the 3:2 polyrhythm, that by doing some elementary things with them, even if they're purely mathematical, you often end up with an ordinary existing piece of drumming vocabulary. So I'll work through this and see what we get.

Update: After having played through this, the results are nothing special playing-wise— we get a Latin-type rhythm in 4/4 with a dotted quarter rhythm happening. I found it difficult to perceive the Afro 6-ness of it. See just below for something interesting though.

First, here's the Afro 6 bell pattern, written in its usual 6/8, and in 3/4:

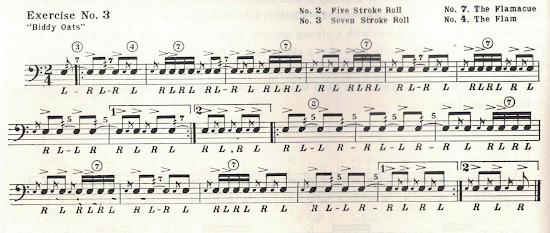

Working on p. 38 in Syncopation with a student, I noticed there were two measures that were very similar to that 3/4 version, the second measure is just extended by two beats:

Update: Apparently a common Brazilian rhythm, according to Ed Uribe. And notice that in the 6/8 rhythm the last beat is the same as the first beat— if we extended the 3/4 pattern that way, by adding the beginning notes at the end, we'd get this very familiar Latin rhythm:

So what happens if play that over a dotted quarter note rhythm, like 6/8— to make it fit I have to write it in 16/8— two measures of 8/8. It's that 6/8 rhythm above exactly, plus some extra stuff at the end:

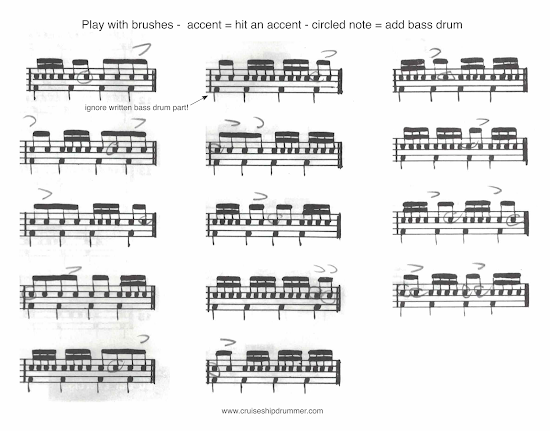

Play this pattern to get a feel for that type of phrasing. Count it in 4, and also count it with the beats I've marked in— 1&a 2&a 3&a 4&a 5e&a:

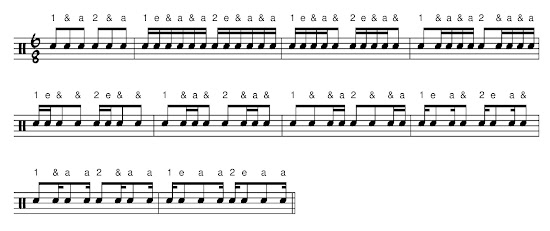

Here's that 16/8 rhythm written in 4/4, as a drum pattern:

Adding hihat— on beats 2 and 4, and suggesting a waltz type phrasing— 3/4+3/4+2/4:

Here we'll play the rhythm with the right on a cymbal, and fill in the remaining 8th notes with the left hand on the snare. Here's that, hands only, and with bass drum added, and with hihat added:

It's also instructive to look at the filled-in original Afro groove as 5/8+7/8— alternating sticking, with each part starting with the right hand: RLRLR-RLRLRLR

With our thing that would have to be 5/8+11/8— RLRLR-RLRLRLRLRLR. You could count it the way I've indicated:

Adding bass drum on all the Rs except the last one, and on the first and last Rs only:

Here are those written in 4/4, with hihat added on the second one:

Back to the original 6/8 rhythm— adding a drum corresponding to all the Rs above but the last one gives us the Rumba clave rhythm:

Here's the same thing in our 16/8 pattern— the left hand part is the “clave” of the made-up item we're looking at today:

Absent the dotted quarter groove it's similar to a

partido alto rhythm. I won't get into it here, but it's how these things work. Things tend to connect with each other. I won't be shocked if I stumble on, or if someone else informs me of, existing music similar to any of this stuff.

Get the pdf if you want to play through all of this. There are a few page o' coordination style practice patterns there as well.

A lot of learn about rhythm here, and meter, and about how things are orchestrated on the drum set. When you're operating essentially within a western music system, this is the level you have to get into with rhythm— consciously or not— to not just be boxed in by its structure.