|

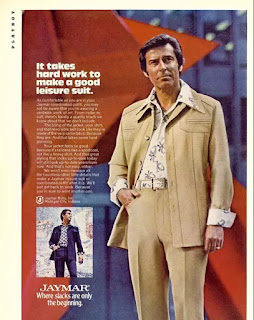

| Is this what you want us to be, Bishop? |

In my thinking, the modern era of our instrument, the drum set, runs from roughly 1945 to 2017; about 70 years. On the blog we're most interested in the middle 40, about 1955-1995. In the mid to late 40s, the drumset became more or less standardized in its modern form, and the language of drumming evolved into what we currently use— even when playing earlier music, drummers now largely use language developed in the 40s. At that point drummers became perhaps more pure musicians— the players we like to follow had mostly lost the show drumming and Vaudeville elements that were a feature of earlier playing. And the actual style of music played then is still played today— bebop is regarded as the foundational style for jazz musicians, and it's widely taught in college. Also in the late 40s the LP format was first used to record jazz, allowing each side of a record to be more than 3 minutes long. At the same time recording technology improved fidelity to the point where engineers could record full drum sets played normally, and the drums could be heard clearly on the recording.

|

| We are not enamored with fedoras literally or metaphorically. |

Since we're into the job of playing the drums, we also are most interested in music that highlights that— a drummer playing a complete tune from beginning to end. We also like a fairly natural sound, in which we can visualize the actual performance. That's the reason we don't really get into much drumming involving a lot of electronics, or sampling, or very artificial production and processing— all increasingly prevalent since the 80s.

So what does this mean for us as artists? If we're just into music from 40-50 years ago, aren't we going to sound old fashioned? Aren't we just doing things that have been done?

Not really. Whatever is the formal history of something you play, you're playing it in the moment, in interaction with other players, in the context of a living musical event. And present drumming is heavily reliant on the drumming of the 60s, 70s, and 80s. Sampling has made drumming stylistically of that period directly relevant to modern music. The actual content of modern drumming has not radically advanced; things played by, say, Tony Williams or Jack Dejohnette or Jon Christensen in the 60s or 70s are conceptually as modern as anything played since.

|

| Once the future of men's fashion. |

There have been, and continue to be many great, individualistic players working more or less within a language and concept developed in the 60s-80s. It's not a problem. Painters did not stop painting after the 1950s, by which time the frontiers of what could be done with pigment on a two-dimensional surface had been fully explored. The historical imperative to do the next most formally radical thing is exhausted, and people are free to paint what they want, drawing from the entire history of the medium.

No comments:

Post a Comment